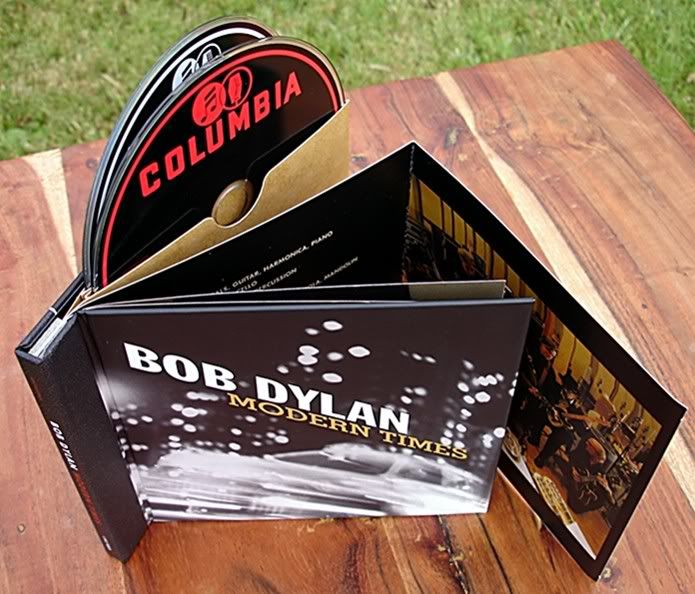

Bob Dylan's 32nd studio album was released 29th August, 2006. It was greeted with almost universal critical praise, but how does it hold up two years later? And how have the individual songs fared in live performance?

Modern Times was released at the high point of a tide of critical praise that had been rising ever since Bob's brush with death in 1997 reminded critics, many of whom had been bashing Dylan's work since as far back as the release of Renaldo & Clara, that Dylan would not be always there for them to take for granted, and that we ought to celebrate his achievements while we still have him. With the subsequent release of the Grammy-winning Time Out of Mind there began a period in which Dylan's critical stock rose so high that nowadays he is in receipt of praise that is almost as undiscriminating as the critical brickbats levelled at him in the eighties and early nineties. One of the few dissenting voices in the general chorus of praise for Modern Times, Alex Petridis in The Guardian, wrote waspishly: "It's hard to hear the music of Modern Times over the inevitable standing ovation and the thuds of middle-aged critics swooning in awe."

Two years later it is even more apparent that Petridis has a point. A solid achievement, Modern Times must be counted a relative disappointment compared to its illustrious predecessor "Love and Theft", Dylan's finest album since Blood on the Tracks and Desire in the mid-seventies. The quality that "Love and Theft" had in abundance was Dionysian energy: so welcome after the ennui and existential angst that had marked all Dylan's work since Infidels. Indeed, this ennervating ennui really begins with Don't Fall Apart on Me Tonight on the album just mentioned:

I wish I'd been a doctor

Maybe I'd have save some lives that have been lost

Maybe I'd have done some good in the world

'Stead of burning every bridge I've crossed.

Fine lines, undoubtedly, but a Dylan who looks back, and especially one who looks back with such despair and disappointment, is an unrecognizable shell of the energetic, questing, Dionysian figure of his best work. By contrast on Blood on the Tracks the singer plumbs the depths of despair, but drags from it the Lear-like rage of Idiot Wind and with Buckets of Rain, learns Lear's lesson of Stoic patience also.

This existential ennui came in Dylan's late middle age at the end of a period of great creative achievement from 1974 through 1983, and from there on becomes the dominant note of his work; think of songs like When the Night Comes Falling From the Sky and Dark Eyes on Empire Burlesque and What Good Am I? , What Is It You Wanted?, and Shooting Star on Oh Mercy, in which Bob basically repeats the same mantra over and over: he knows no answers, he has no hope, he lives companionless in a world apart where "life and death are memorized." All these negative feelings reach their peak of artistic expression on Time Out of Mind, which contains what may be the most negative, nihilist line in his entire output:

Well my sense of humanity has gone down the drain

Behind every beautiful thing there's been some kind of pain

She wrote me a letter and she wrote it so kind

She put down in writing what was in her mind

I just don't see why I should even care

It's not dark yet, but it's getting there

When I first heard the line I've marked in bold, I found it so upsetting and depressing that it took me a long time to appreciate the real artistic achievement of Time Out of Mind, which is to state in the starkest form yet the existential ennui that had been overpowering Dylan's work since the mid-eighties. In that sense, it performs the same function as did Watching the River Flow, which faced up to the loss of his muse in the midst of his domestic content with its disarming opening line: "What's the matter with me? I don't have much to say." A Dylan who doesn't care, who is indifferent to love and desire, and who relies on negativity to pull him through is not the Dylan who once declared "this music that I’ve always played is a healing kind of music" and who wrote

Desire... never fearful

Finally faithful

It will guide me well

across all bridges

inside all tunnels

never fallin’.

A spiritual sickness hangs over Time Out of Mind from its opening lines, and it is only reinforced by the album's grim focus on physical decay: scars that won't heal, flesh falling off the singer's face, every nerve so vacant and numb. When he sings "But my heart just won't give in", you get the sense that he only wishes it would. Highlands, which does have its moments of humour and relief, nevertheless leaves us with a portrait of the singer as an old man shuffling along the street, talking to himself, and envying the younger people from whose unselfconscious joys and laughter he is forever banished:

I see people in the park forgetting their troubles and woes

They're drinking and dancing, wearing bright colored clothes

All the young men with their young women looking so good

Well, I'd trade places with any of them

In a minute, if I could

So in the 14 years since Don't Fall Apart on Me Tonight, Dylan has gone precisely nowhere: still wishing he were living someone else's life, looking back with regret and despair.

The achievement of Time Out of Mind, as heretofore stated, is to state these negative feelings in unpredecentedly stark terms. But the album marks a dead end: he cannot go forward artistically by simply restating over and over these feelings of existential isolation, of negativity and regret.

That is why "Love and Theft" was such a spectacular achievement. It has an energy and vitality not heard in any Dylan song probably since Jokerman and the brilliant, underrated Tell Me in the Infidels sessions. Gone is the companionless, misanthropic singer of Dark Eyes, Not Dark Yet, and Highlands; the singer on this album shows himself still receptive to feelings of love, friendship, and gratitude:

Well my ship's been split to splinters and it's sinking fast

I'm drownin' in the poison, got no future, got no past

But my heart is not weary, it's light and it's free

I've got nothin' but affection for all those who've sailed with me

(Of course, these lines are from Mississippi, which was written for the Time Out of Mind album; and that album's atmosphere of bleak misanthropy and spiritual ennui would have been considerably relieved by that song's inclusion, as Dylan intended. Unfortunately, he and producer Daniel Lanois could not see eye to eye on the song's production, and so the song was dropped from the album. The original recording of Mississippi is to appear on the forthcoming Bootleg Series collection of outtakes, Tell Tale Signs.)

Best of all, perhaps, is the brilliant jump blues Summer Days, a song that could not have appeared on Time Out of Mind. In contrast to the despairing resignation of Not Dark Yet, which dolefully accepted that "it's not dark yet, but it's getting there", the singer of Summer Days reminds us of Dylan Thomas's "Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night":

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

But rather than raging against the dying of the light, the singer of Summer Days dances against it, leaping on the table to propose a toast to the King, and declaring that though summer days and nights are gone, that doesn't mean that there is no more fun to be had. The Dionysian energy of this singer is more like the Dylan we know of old, one busy being born rather than busy dying.

The energy, high spirits, and perhaps most welcome of all, the humour of "Love and Theft" made it Dylan's finest album for over 20 years. It sparkles with wit, and contains more quotable lines than any album since Street-Legal. It was perhaps too much to hope that Modern Times could equal this standard. But refreshingly, there is no relapse into the doldrums of most of Dylan's post-Infidels output. Most welcome is the extension of Dylan's musical palate beyond his usual reliance on blues and ballad forms, although there are some disappointingly generic blues shuffles on this album also (a couple of which border on musical plagiarism). Not since the underrated Shot of Love has Dylan dipped so much into the rich waters of American popular music. A particular source is pre-rock pop of the twenties to the fifties. Bing Crosby is a particularly strong influence; "When the Deal Goes Down" is musically a chord-by-chord recreation of Bing's "Where the Blue of the Night Meets the Gold of the Day" and "Beyond the Horizon" lifts the tune of "Red Sails in the Sunset." Moreover, Bing's version of "Brother, Can you Spare A Dime?" (played by Bob on the Theme Time Radio Hour show "Rich Man, Poor Man") hangs over Workingman Blues #2. How much love and how much theft lies in all these borrowings has been furiously debated.

One of the most pleasing aspects of "Love and Theft" was its cheerful sexuality, as in the artful suggestion of waning potency in Summer Days:

My dogs are barking, there must be someone around

My dogs are barking, there must be someone around

I got my hammer ringin', pretty baby, but the nails ain't goin' down

or this saucy invitation in High Water (for Charley Patton):

Got a cravin' love for blazing speed

Got a hopped up Mustang Ford

Jump into the wagon, love, throw your panties overboard

And best of all, this allusive third-person reference:

It must have been Don Pasquale makin' a two a.m. booty call

Don Pasquale is the eponymous character in Donizetti's opera buffa, based on the commedia dell'arte archetype of the vain and foolish old man who tries to thwart the young heroine's love for the hero by marrying her himself. With a touch of comic genius Dylan has this stock character paying a "2 a.m. booty call"; and the pounding on the walls suggests that this Don Pasquale is no impotent figure of fun, but a virile figure capable of satisfying his younger lover.

By contrast, the sexuality on Modern Times comes over as idle boasting or even slightly creepy, as in the shout out to Alicia Keys in Thunder on the Mountain and in the unpleasantly sexist line "I want some real good woman to do just what I say" in the same song, in which the singer studies Ovid's Art of Love and proclaims "here's hot stuff here and it's everywhere I go." Unlike Don Pasquale who is getting on with it, paying his booty call, the singer of Thunder on the Mountain is just beating on his trumpet, or rather blowing his trombone (a rather obvious sexual metaphor).

Compare also the confident strut of Cry A While on "Love and Theft":

Well, there's preachers in the pulpits and babies in the cribs

I'm longin' for that sweet fat that sticks to your ribs

I'm gonna buy me a barrel of whiskey - I'll die before I turn senile

and the same song's earlier line about feeling like a fighting rooster with the much less convincing boast in Spirit on the Water:

You think I'm over the hill

You think I'm past my prime

Let me see what you got

We can have a whoppin' good time

That corny and dated phrase "whoppin' good time" is the antithesis of Don Pasquale's ultra-hip "booty call" and rather deflates the intended boast. Rather than as the still virile aging stud that the singer intends to present himself as, he comes over more like a paunchy dad trying to dance at his daughter's wedding reception.

Dylan does improve this verse considerably in concert by singing the first two lines as questions, with an implied "Oh yeah?!", invariably getting a reaction from the audience. And this viagra-induced boasting is at least an improvement on the indifference to desire manifest on Time Out of Mind.

Another weakness of Modern Times compared to its predecessor is its rather precious and somewhat stilted lyricism that at times borders on Victorian pastiche, especially in the parlour ballad When the Deal Goes Down and Spirit on the Water. This may be due to Dylan's falling under the spell of the Civil War poet Henry Timrod (reflected in several borrowings from the earlier poet's work). Compare the freshness of these lines from Moonlight:

The clouds are turnin' crimson

The leaves fall from the limbs an'

The branches cast their shadows over stone

Won't you meet me out in the moonlight alone?

The boulevards of cypress trees

The masquerades of birds and bees

The petals, pink and white, the wind has blown

Won't you meet me out in the moonlight alone?

The trailing moss and mystic glow

Purple blossoms soft as snow

My tears keep flowing to the sea

Doctor, lawyer, Indian chief

It takes a thief to catch a thief

For whom does the bell toll for, love? It tolls for you and me

I picked up a rose and it poked through my clothes

I followed the winding stream

I heard the deafening noise, I felt transient joys

I know they're not what they seem

In this earthly domain, full of disappointment and pain

You'll never see me frown

I owe my heart to you, and that's sayin' it true

And I'll be with you when the deal goes down

which undoubtedly have a certain charm, but border on pastiche.

Against this, Modern Times has strengths of his own. It is much better sung than its predecessor (though the musicianship is not of a similarly high standard), and its three best songs are outstanding. The first, Workingman Blues #2, is the closest the album gets to evoking the spirit of Charlie Chaplin's Modern Times. The

song features some of the strongest, most evocative writing of the album, for instance, in this reminder that all of us, rich or poor, walk in the valley of the shadow of death:

The opening lines seem to have an extra topical relevance as the world's economy goes into recession:

There's an evenin' haze settlin' over the town

Starlight by the edge of the creek

The buyin' power of the proletariat's gone down

Money's gettin' shallow and weak

The place I love best is a sweet memory

It's a new path that we trod

They say low wages are a reality

If we want to compete abroad

However, this is no rewrite of North Country Blues or Hollis Brown. Its narrative element is non-linear and its protagonist's situation more complex; whoever the singer is supposed to be, he is hardly the typical working man. Dylan is unlikely to usurp Springsteen's status as the poet laureate of the blue collar worker. It's a complex song full of strong images, memorable lines, and with a rousing chorus.

Even more impressive is Nettie Moore, one of Dylan's great ballads, and a song that he has invariably interprets powerfully in concert. A notable feature of the song, despite its folk ballad form, is its saturation in the language of the blues. The opening line quotes the old song "Lost John":

Lost John standin' by the railroad track

Waitin' for the freight train to come back

while later lines evoke the famous story of Frankie and Albert. The crossroads where Robert Johnson is said to have sold his soul to the devil is also evoked. As with many of Dylan's recent songs, it is difficult to say what this collage of recollected and original lines means, but the song is undoubtedly highly evocative.

And finally, the album's closer Ain't Talkin', a mysterious and somewhat sinister epic that returns us to some extent to the atmosphere of Time Out of Mind. The claim that Modern Times was the final album of a trilogy stemmed from his record label rather than the artist himself; in fact, Dylan has specifically denied it. Nevertheless, this dark tale of a man walking, walking, walking, until he reaches the edge of the world (which he appears to doubt is round as men say) brings us full circle to the earlier album, which opens with the words "I'm walking..." and thereafter uses the image of the singer walking "a thousand miles from home" (or rather a million miles) repeatedly as a symbol of his isolation from society. The song begins with a reminiscence of the story of Mary Magdalene mistaking the risen Christ for the gardener of the grounds; but this "mystic" garden is a place of violent menace where "wounded" flowers hang from the vine and the singer is struck from behind. The singer himself threatens to slaughter his enemies if he ever catches them sleeping. He is not alone (which separates him from the isolated figure of TOOM, who seems more of an autobiographical than the mysterious narrator of "Ain't Talkin'), but accompanied by a band of brothers who "share my code", a faith that's long been abandoned, as he walks through a world of hostile infidels and "cities of the plague". The song raises more questions than it answers, and when the narrator steps off the end of the world in the song's final lines, we still have no idea who he is supposed to represent. Several lines in the grim discursive narrative are borrowed from Ovid's self-pitying letters from his exile on the Black Sea, the Tristia, but the story seems closer to Homeric epic than classical elegy. Although it raises more questions than it answers, as a performance it is gripping, full of menace, horror, and intensity.

I leave you with videos of these three songs, each of them a classic of the modern Dylan.

Workingman Blues #2 was a song Bob found difficult to make effective in its first year of live performance. It wasn't until the Australian tour of 2007 that the song really came into its own. It is now a regular concert standout. The following video is identified only as "live 2008"; great sound, though poor video.

Here's a fine Nettie Moore from 2006:

And here's my favourite performance of Ain't Talkin' (Melbourne, Australia 19th August, 2007):

2 comments:

Very nicely written. I don't analyse the albums as much as you do, just enjoy them, but I admire your review and learned from it.

I somehow missed this excellent post- just reading now-- great work! I think you capture the pros and cons of this album well... you might want to put in a ps about the 'new' version of 'someday baby' as well as some of the other recent songs that have surfaced in telltale signs, tho that's a whole other post I guess. Keep up the good work! - Mike S

Post a Comment